CHAPTER 1: How I became a Divemaster during 2020's Global Lockdown.

It was the start of 2020, which was the year when Covid-19 loomed out of an unforeseen abyss to fuck with us all.

My mission had been to explore the Philippines: a mighty southeast asian archipelago of some seven thousand, six hundred and forty one islands.

The islands range from tiny islets with just a few palm trees, to vast plateaus of rice paddy land, painted grey with bustling cities that fall against a backdrop of active volcanos and jungle covered mountains.

But the tropical waters surrounding these islands were my main objective.

Because it’s so much less developed than much of the rest of the world, the Philippines is rarely visited, making it perfect for pushing the boundaries of scuba exploration.

Flying out of the UK and into Manila half way through March, I was vaguely aware of the novel coronavirus threat brewing in China; but back then it still seemed like a distant shadow that couldn’t possibly screw over the entire world as it came to.

Landing on the Philippine’s largest island: Luzon, in it’s capital city: Manilla, I initially planned to trek across the Rizal mountain range, before catching a ferry to the next big island down: Mindoro to train as a divemaster in Puerto Galera.

After that, I’d head down south to the mysterious southern region of the Philippines; where untouched beaches and undiscovered dive sites await.

I’d film the entire thing and turn it into a movie. That was the plan. Alas. It didn’t happen. Here’s what did:th

I was still in Manilla and had no plans to leave for another week; when I saw the news: in twelve hours, the entire city would go into lockdown, with nobody allowed in or out.

Like any big city, Manilla would be a bad place to get holed up in during a sudden pandemic; with it’s endless crowds, masses of poverty and limited food, it would be a difficult place to survive in, if coronavirus did indeed turn people into zombies.

I switched off the news, cancelled the next two weeks worth of plans, packed my shit and jumped on a night bus to Batangas from where I could catch a ferry to Mindoro; an island so sparsely populated that hunter-gatherer tribes still roamed freely in the mountains, surviving off of nature. If society collapsed, I could go and be one with the tree people.

Waiting at the overcrowded bus stop in Manilla was like something from the first few minutes of a zombie flick. For hours, I stood in a que that poured out of the building and onto the streets; countless Filipinos clutching every belonging they could and anxiously peeping out from behind facemasks, in a frantic bid to leave the city before nobody was allowed in or out.

It was not easy finding a space on that night bus. Things got ugly as everyone tried to squeeze inside. At one point, I was forced to use someone’s granny like a club, swinging the shrieking old lady wildly over my head, in order to beat away the small filipino family trying to take the seats that I wanted to put my feet on – but luckily I survived.

Arriving at Batangas port five hours later, I discovered there were already hundreds of people asleep on the ground, waiting for the morning to bring the first ferry of the last day before the port closed.

“Oh no – god-fucking-DAMNIT“!! Exclaimed I, drawing attention from several curious passers by, as I dropped to my knees and beat my chest like a feral gorilla “With so many good folk ahead of me and such a tiny port, I’ll never get on the ferry to Puerto Galera in time – even if I had weeks”!

Later that day, as the ferry that I was on pulled into Puerto Galera Bay, I found myself staring up at the lush mountains of Mindoro, where vibrant jungle tore up behind the sand like a wave of neon green fire ripping backwards deep into the island.

Tropical bird song filled the air whilst the clear waters gently slurped against the sides of the ferry as we pulled into Puerto Galera port to be greeted by a team of officials; whom questioned each of us about where we’d been, for what essential reason we were here and if any of us were feeling at all covid-ish.

Lying my way through, I caught a tricycle from Puerto Galera to the tiny, vaguely tree shaped Sabang peninsular which juts out from the central northern tip of the rest of Mindoro and at just five kilometres squared, is over two thousand times smaller than the rest of the island, yet the soul location of every last one of it’s dive resorts and sites.

After a ride that was shaky, loud and hot as only a tricycle journey can be, along a winding road that literally cut through steaming hillside jungle, I was stepping out of the rickety motorcycle side-mount and into the concrete heart of Sabang Barangay; once a small and sleepy fishing village, now very much the central hub of tourist infrastructure, with it’s market shop and chemist, spattering of hotels, handful of open air restaurants, dimly lit girly bars and tourist stands lining either side of a single, pothole riddled road.

I heaved my rucksack and pushed my way through the small crowd of old ladies selling beads, shifty looking fellows that might have some weed, tour stand agents gesticulating for me to step closer, running children; scrappy dogs, mangy cats and at least a dozen other tricycle riders asking if I’d care to catch a ride in their tricycle, despite having clearly just gotten out of one moments before.

Several hundred yards later, I’d reached the end of the cracked road and left the beehive drone of voices and colourful stores behind. Now all that lay ahead of me was the split of a forked path, directly ahead of which lay a six foot drop to the white sand beach below, which was known as Sabang Beach. Out in the distance across the sea, I could easily make out the distant jagged mountains of the Batangas province on Luzon island (which was where I’d come from), as well as the small but ever lush Verde island and the slightly larger Marikaban island, both of which lay sprawled in the glistening ocean between Luzon and Puerto Galera like strips of rugged green, complete with their own small mountains, rising less than a thousand meters into the clear blue sky.

I knew I had to turn left so that’s what I did, tramping along the hot yellow cement path, sweat already pouring down my forehead and into my eyes as the stiflingly humid air clambered over my skin like a prickly swarm of ants.

It was not a long walk. First I went to the end of Sabang Beach with it’s clutter of tiny stores and beach front bars, then up and over some steps into Small Lalaguna beach, which was much quieter, being defined only by a few lifeless looking resorts that were split apart by narrow gaps that wove between them to mark the alleys of local homes. A few children splashed about in the shallows, whilst further out tiny fishing boats skimmed across the still ocean like giant water-boatmen.

Passing up and down some steps that wound around a rocky outcrop of cliff that was crowned by a spattering of jungle, I came into Big Lalaguna beach, which I immediately liked the best of all the beaches. It was the quietest one as well as the smallest. It was also the cleanest; which was quickly apparent from the mesmerisingly clear waters that slurped against it’s white sands (I learned later that this was because Scandi Resort was the only place to have installed a sewage treatment system, to protect the immediate marine environment). There was no path here, just sand broken up by the odd strip of cement lining the steps of a resort here and there.

At the far end of Big Lalaguna, lay another palm tree topped cliffy outcrop; which combined with the one I’d just come around, penned Big Lalaguna in, hiding the rest of the Sabang peninsular from view so that it felt as if this place was somehow separate from the rest of the world. I walked for a couple more minutes until I found myself standing in the middle of the beach staring up at my final destination: Scandi Divers Resort

The first person to greet me was one Mr. Luke Spence; the resort’s diving staff instructor and a fellow Brit; he hailed from North Yorkshire and was a true born northerner right down to his accent and easy going mannerisms. I immediately got sound vibes off Luke, although we didn’t become properly acquainted just yet.

I was shown around the resort: starting with the ground level restaurant serving a variety of western and oriental dishes; which fused into the camera room and gear space where dozens of scuba tanks, masks on racks, fins, booties, wetsuits, bcd’s and regulators stood to attention next to wash basins and a bench for easy kitting up; all within earshot of the waves out front gently knocking against the two tied scandi diving skiffs.

Around the back was a small swimming pool and up some steps lay a second restaurant; with more steps leading to a third bar and dining place: the well known Scandi Sky Bar, which gave the very best view of the entire Big Lalaguna beach yet and the rippling blue ocean stretching off into the distant mountainous shoreline of Luzon directly ahead. Way further back on Luzon, it was even possible to make out the tiny conical silhouette of Taal volcano some fifty kilometres away (which was fortunately devoid of any red glow or smoke). I stood leaning over the sky bar banister with an icy beer in hand whilst my lodgings were prepared, watching the general goings on of Scandi Divers Resort.

Besides Luke, the staff were all Filipino and they were very friendly and full of banter, joking around with one another like very old friends, which I later found out they were as almost the entire team at Scandi are Puerto Galera locals who’ve lived together since childhood. Although I was not fully aware of it just yet, Scandi Divers was to become the most friendly and laid back resort I’ve stayed in yet.

It wasn’t long before it was time to be shown to my room. I’d chosen the magnificent, second floor level ocean suite which in addition to being a ten second walk from the restaurant had it’s own private, ocean facing balcony, a kingsized bed, a kitchen with a huge plasma screen tv, an ensuite shower room – and like all the social areas of Scandi Resort, was tactfully decorated with various posters for vintage diving themed movies with titles such as “The Mermaids of Catan”, “Creature of the Black Lagoon” and “Man-Eater”.

There was also a lot of extra space in the ocean suite, allowing me to effortlessly unpack in my normal fashion which is to pour all the contents of my bags across the floor and beds, covering every spare inch of space and thereby allowing me to see all of my stuff at any one given time. After accomplishing this, which took about ten seconds, I wandered over to the second floor bar restaurant to see what was afoot.

As things currently stood, although Manilla city back on the mainland had gone into a full lockdown as of that morning, with people restricted from even leaving their homes; in other provinces there had been no official set of rules for what was and wasn’t allowed, besides a halt of public transportation between regions. Subsequently; because it was the Philippines that we were in, with no clear set of do’s and don’ts, things were more or less continuing as normal at least in Puerto Galera; with restaurants, nightlife and diving still ongoing.

For who knew how long. Which was the conversational theme of that afternoon, as what appeared to be the majority of the guests at Scandi Divers resort assembled in the second floor restaurant and proceeded to attempt to outdrink and un-think the ever growing covid-19 issue that just a few weeks ago had seemed like a poorly timed and in bad taste April fools joke, yet now threatened to ruin everyones plans and who knew what else.

There were a couple dozen or so other guests, including a particularly love stricken German couple who actually got engaged several days later, an Aussie couple who worked as paramedics and were not looking forward to returning to work, an exceptionally loud-mouthed group of Americans whom I was concerned might drink the bar dry before I could and several other quite large groups who did not seem to make much effort to interact with anyone not directly from their own clan or perhaps they just didn’t speak english.

Here and there I made small talk with the other guests, but for the most part I simply lurked in the shadows and drank rather heavily as I listened to what everyone else had to say.

As it was, there were a fair amount of theories floating around as to what had caused the dreaded Covid-19, ranging from government conspiracy, to 5G, act of God, force of nature, evil plot conjured up by super-villain Bill Gates to force the population into lethal nano-bot infused inoculations and just about everything else you could care to hear, but couldn’t quite believe you were hearing.

Accompanying all this was a great deal of talk among guests about what was the most sensible thing to do next. A fair few, myself included, were still hopeful that this would somehow all blow away in the coming weeks; whereas others seemed convinced that now might be the last window to get out of the Philippines and return home before all flights were suspended.

This second opinion was the most popular and it seemed that even though scuba diving and general activities had not stopped in Puerto Galera just yet, people were itching to leave whilst they still had a guarantee that it was possible to do so. From the sounds of it, Scandi Resort was going to become a lot more empty in the next few days. As I stared out at the setting sun which reflected off the ocean to make it resemble lava, and listened to the gentle sigh of the waves, I resolved that now I had arrived in the Philippines there was nothing that could possibly make me leave again out of my own free will.

Over the next few days the number of guests at Scandi Resort dwindled until the staff outnumbered us, though some still remained and for those first few days scuba diving and even the nightlife carried on, unperturbed.

During that time, I didn’t make a single dive. Whilst in Manila, I’d visited the legendary Ace Tacud to get a tattoo of fish and other sea creatures swimming over my chest. For any tattoo to properly heal, you need to wait fourteen days before immersing it in water and I had five more to go before reaching that minimum threshold. Ah sweet irony, as you’ll come to see.

Besides, I still had several online missions to complete with Diving Squad, so for those first few days I sat in the restaurant, mashing the keys of my macbook and eagerly anticipated my upcoming first splash. Life has a funny way of piecing together events and decisions you’ve made into the most ironic outcomes possible.

Just two days before I’d reached that fourteen day mark since getting inked, I was eagerly following Luke around as he casually strolled through the dive shop, explaining to me the various procedures to organise dives for guests, as much of my divemaster training would be to act as an assistant on hand aka “tank bitch” to the dive staff; someone who could carry other guests’ gear (especially their air tanks) and help them into it, give dive briefings, help out underwater and so forth.

These elements of the divemaster training came alongside unlimited fun dives, learning how to teach each of the scuba skills required for someone to pass their PADI open water course, various new skills to learn myself such as underwater search and recovery and underwater mapping, endless theory with written examinations at the end…and before I even started on any of that I still had my rescue diver course to complete first, which would take me through everything from special in-water tows, dealing with panicked divers, dealing with unconscious divers underwater, carrying people out of water onto the shore or lifting them up into a boat, recognising signs of nervous divers, providing care for decompression sickness also known as “the bends” – (dreaded by all) and then some more. It sounded like it was going to be a tough but unforgettable experience. I was chomping at the reg to start.

Luke also showed me the rentable scuba gear from which I was allowed to assemble my own personal kit, as I still had not gotten around to buying my own yet and the diving stores were all closed now. In to my name-tagged crate went what were to be my booties, fins, mask, bcd, regulator and dive belt for the next few months of diving. Upon that final item entering the box, we heard a crackle of distorted Tagalog (the most common language spoken in the Philippines) via megaphone as a government official mooched up and down the beach making some sort of decleration. “That doesn’t sound good” said Luke and briefly wandered off to find one of the staff to translate.

“It’s bad” he said upon returning several minutes later before explaining to me that basically it was like this: Puerto Galera and indeed the entire Philippines, were now to join Manila by going into an “enhanced community quarantine”, which was basically the fancy way of saying the strictest lockdown possible – and unbeknown to us at that moment, one that would go on to be one of the longest and strictest lockdowns in the world, one that in parts of the country would maintain it’s “enhanced” status for over half a year.

What this meant was the closing of all restaurants, bars, recreational areas, public areas and most work spaces; the forbidding of anyone to leave their home other than to buy food and only with a quarantine card, no trekking, no swimming, no scuba diving and topping it all of, the Philippines was unique in the world in that they decided to compliment their enhanced community lockdown with an alcohol ban. (The alleged reason for this was the fear that people would spend what little money they had on alcohol rather than food, but at the time I was not thinking about this and believe me when I say, I’ve still never met a filipino who saw a shred of sense in their nations liquor ban of 2020).

After the news had broken, everyone disappeared back inside their rooms. To my surprise, Luke reappeared at mine thirty minutes later, wearing his signature scuba diving themed tanktop (which all of his tops seemed to be) and PADI cap.

Around his shoulder was slung a waterproof blue backpack from which he produced, even more to my surprise, a playstation 4 and a dozen games. “You’ll be wanting this”. He said, adding that he had a PS5 and dozens more games back at his so it was really no trouble at all.

Luke also had a small pile of rather thick looking books tucked under one arm which moments later lay scattered unceremoniously across my room. I had now become the proud owner of the PADI “Rescue Diver Manual” “Divemaster Manual”, “Instructor Manual” and “Encyclopaedia of Recreational Diving”, as well as the “Emergency First Response Primary & Secondary Care Manual” and an illustrated guide to identifying marine species within the Indo-Pacific region.

Although I didn’t saying anything aloud the expression on my face must have spoken plainly enough because Luke chuckled. “Yeah there’s a lot of reading involved. You’ll need to read the manuals, complete the knowledge assessments and reviews after each chapter as well as take some marked exams at the end. Might as well get cracking on it now, so that when we can dive again there’s no distractions right”?

I nodded, reluctantly – and Luke disappeared again. For a while I flicked through the books and then tried my hand at the playstation 4 with “The Last of Us”, which seemed a fairly ironic choice on account of the fact that in this game the entire world was also going to shit due to a virus; in this case one that transformed people into fungal zombies. For a while I crept down bleak, post-apocalyptic city streets, blasting my few scavenged revolver rounds at screeching fiends with bloody faces that had been split apart by mushroom like growths coming out of them. At one point, I found myself travelling through a stronghold in which soldiers were dragging random people out of buildings to test them as a loudspeaker ordered others to stay in their homes due to an enforced lockdown. I turned the game off. It was a little too familiar for right now.

As I stood alone on my ocean facing balcony that evening, I saw the first armed patrol march past to make sure everyone was staying inside, assault rifles slung over their shoulders and bouncing slightly as the tough as nails looking soldiers beamed over and waved hello at me in typical friendly filipino greeting.

By this point, you may be thinking that things were starting to look pretty grim but here’s the thing: I was still in Puerto Galera. And although there was a good deal of frustration, stagnation and exasperation ahead; things were not going to be as difficult as they would have been in Metro Manilla – or even the UK for that matter or many other parts of Europe during those early months. In fact, I found myself drinking up on the sky bar with Gary, Dave, Luke and the other remaining guests that very night.

You see, the Sabang Peninsular that I now confined to was a tiny, cut off speck within the very sparsely populated province of Mindoro Oriental on one of the Philippines least developed islands, Mindoro – where indigenous tribes still danced about just over the mountains.

Electricity outages were common, running water couldn’t be drunk and like aircon, WiFi was a luxury thing possessed only by resorts meaning that real news travelled slow.

For many locals there was no way they could adhere to all the suddenly imposed restrictions the entire time. Over half of them relied on some member of their family to hop in a tiny fishing boat and skim out across the sea each morning just to be sure of getting something else for supper besides rice.

Plus it was a beach community; which in most parts of the world tend to have a more laid back and casual approach to matters. With a singular track, that in places faded to just sand, being the only way along the beaches, the armed patrols; which turned out to be pretty infrequent – could be seen from several hundred meters away, giving anyone in the sea ample time to nip off down a side alley and back into their home, whenever soldiers were spotted.

All in all, this meant that whilst Manila would experience a fully enforced lockdown that didn’t budge for months, this was not to be the case for the more far flung areas like Puerto Galera, which instead wavered between strict and not so strict on a weekly basis.

Public spaces and tourist attractions remained closed and I heard of a few individuals getting arrested for breaking the 7pm curfew, but no one met a sticky end for taking a stroll so long as it was in daylight hours and they didn’t stray beyond one of their armed checkpoints – nor for dipping their toe in the sea.

Fortunately, resorts like Scandi were allowed to continue hosting any guests they had left, even if they had to close their public spaces and couldn’t permit scuba diving.

Over the first few days after Puerto Galera’s lockdown began, most of the Scandi staff were sent home to wait out the restrictions with their families – but a few stayed at the resort, to guard it’s rice supplies and tend to us few remaining guests meaning that some member of that noble skeleton crew was always manning the kitchen so we never went hungry. The staff maintained their easy going, humble and humorous approach to life and although I’m sure the stress of reduced pay and virtually no freedom was getting to them, it never showed in their faces.

There was always at least two or three of “the boys” in the downstairs restaurant; with so few tasks to complete they could lounge back in the chairs and gaze out across the turquoise waves lapping up Big Lalaguna Beach directly outside – usually laughing, often quite hysterically at the various jokes they constantly told amongst themselves although at other times being content to just gaze out to sea in near silence for hours or play on their phones. Sometimes one of them would have a megaphone which they used to hurl jokes at the half dozen or so local fisherman that’d be just a few hundred meters out to sea – I couldn’t understand what they were saying because it was all in Tagalog but a couple of times someone translated for me and afterwards I knew the general gist of it was helpful comments along the lines of “stop slacking” and “we’re going to eat all your fish as soon as you get back”! which elicited a lot of sniggering from the other Scandi lads.

Within about a week of the enhanced lockdown extending to PG, all of the remaining guests had caught the last flights back to their home countries – save myself and one other guest, Brian; a cheerful American whose love of Trump was exceeded only by his love of women. When he was seen at all, it was usually swaggering about with one or sometimes two dark skinned Filipinas under his chubby arm – slim girls, with cute faces and dark brown eyes that glinted knowingly and hips that wriggled under skirts so short that one had to triple check to be sure that they were there at all. Brian disappeared for days on end and it was clear to all what heinous ways he was finding to pass the time. Who could blame him? I did avoid going in the swimming pool whenever I’d seen him up late the previous night though.

Dave left after a couple of weeks, finally giving into his families pleas for him to return to Chicago their reasoning being, that since he was in his seventies, he ought to be close to the best healthcare possible – so off Dave went, which was a shame because he could always muster a genuine grin, despite the dire current situation for his entire business and he had a lot of interesting facts and stories to tell, but off he went all the same and noone could blame him for it. On the day before he left, Dave lent me his son’s acoustic guitar (along with a book about the political situation in North Korea between the 80’s – early 10’s) so I did always have something to strum in the coming months.

Gary remained and from time to time I would sit before him never saying a word myself (it was impossible to anyway) as I was regaled with epic tales that could easily last an hour and of which there appeared to be an infinite and varied supply, their only binding similarity being that they sounded like they happened in an action movie yet were real life adventures; sagas set in every corner of the world, of business empires and snow skiing championships, celebrity parties and being stranded on islands, diving in lakes to recover crashed WW2 planes and hairy encounters with tribes in Papua New Guinea.

These tales of Gary’s past came along with an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of historical events and key figures from hundreds of years ago to this decade, especially when it was anything that impacted society today or leaning towards a grizzly nature. At this time, I listened to Gary with amazement although I still had no idea who he was or how he had come into possession of so many incredible stories.

Although the bars were closed and alcohol supplies grew scarce, you could still buy something or other if you asked at the right store and on the very first day after lockdown, some forward planning individuals such as myself and Luke bought literally hundreds of san miguel beers and dozens of giant bottles of tandori rum, meaning we were never thirsty but often hungover.

After the first week of lockdown in Puerto Galera – once it had become apparent that we’d get away with it, myself and the yorkshireman began to meet most afternoons and drink a good dozen beers or so each as we watched the sun slowly dip beneath the pink horizon from my balcony, before moving inside when it grew dark to escape the endless swarms of mosquitos and switch from beer to rum and blast through videogames. It turned out that Luke and I had many shared interests and our conversations flowed seamlessly between scuba diving to music, living in england vs living in southeast asia, different cultures, aliens, zombies, people, life and the human condition in general.

Luke also sat through the PADI training videos with me – of which there was one to accompany each chapter in the Divemaster training manual and afterwards tested me on the knowledge assessments, which covered everything from the role of a Divemaster such as supervising diving activities, assisting student divers, risk management and emergency care – to specialised skills and activities, currents, tide and waves and even the business of scuba diving.

It was a fairly odd feeling to be training as a Divemaster but only by watching movies and reading books and without a single actual dive and whenever this fact dawned on me I was subsequently frustrated but for the most part I – and I think Luke, were pleased to have a productive way to fill the time despite how dated the PADI training videos were. Plus the end of each days learning always marked the start of every afternoons drinking. We’d just discovered a new game called Subnautica – in I was also a scuba diver, except now I was diving through an alien sea on another world, filled with all kinds of quirky creatures – some of which I ate, stabbed or splattered with my submarine (they swam out of nowhere) but others that I had to evade to survive, as I continuously searched for food and resources to fix my crashed spacecraft and escape the planet (SPOILERS AHEAD!)…whilst also finding a cure for the deadly alien virus that I had contracted when crash-landing on the distant world – in order to avoid triggering the planets’ extinct sentient races’ planetary defence system that blasted all who were infected out of the sky if they tried to leave – because the theme of 2020 followed everyone everywhere even in the strangest of ways.

One morning, Luke appeared on my patio with a titan mug of coffee and smoking a fag (probably his fifth of the morning); this time wearing a top where Darth Vader’s breathing apparatus had been hooked up to a scuba apparatus with the words “dive side” (Luke later explained that it was meant to say “join the dive side” but it was a custom top that he’d mass ordered for the Scandi dive shop and there’d been a miscommunication at the Chinese factory where they had been made, hence just the words “dive side”. Still a damned fine shirt though, so of course I got one). Anywhom, as Luke took a long draw on his cigarette and slurped at his coffee whilst gazing out to sea, he told me to get my scuba diving gear on.

Now before you get too excited, I want to explain that we were not getting into scuba gear with the intention of setting a toe in the ocean. However, over a month had now passed – it was nearing the end of April and although the lockdown in Puerto Galera still meant the closure of almost all public buildings and technically no gatherings were allowed, it was well established by this point that people could do things like stand in the bars of a resort if they stayed there even after the 7pm curfew , so long as they kept it down- and similarly use the swimming pools of said resort, if it had one – which Scandi Divers Resort did.

And so, as for the first time that year, as I stood fully clad in scuba gear and took one huge goose step forwards in order to make a giant stride entry, it was not tropical waters that rushed around me in refreshing greeting with the bubbles parting way to reveal dazzling coral, but instead the blue square tiles of the two meter deep Scandi swimming pool, which was devoid of life – unless you counted the chlorinated corpses of a few unfortunate insects that had fallen in and were floating about lifelessly.

The reason we were jumping in the pool was to practice a big part of the Divemaster course which is to go back through the same skill circuit that student divers learn when taking their open water dive course.

There are twenty scuba skills that an Open Water Diver must learn, including the giant stride entry, neutral buoyancy test, switching between breathing from a regulator to a snorkel at the surface, the five point descent, the five point ascent, removing and recovering the regulator underwater, the same again with the scuba mask – whilst blowing water out of the mask to clear it afterwards, sharing air with one another through spare regulators, swimming through the water without a mask, removal and recovery – at the surface and underwater of the bcd and the same again for the weight belt, a controlled emergency ascent and a few other things like buoyancy exercises.

Whereas student divers need only perform the skills to adequate level to complete their open water certification, when re-running this skill circuit as a Divemaster, you have to perfect each skill to demonstrable level, including being able to break down and mime the numbered steps towards completing each one and also the things to remember not to do. Eventually the Divemaster course moves onto helping real life student divers with these skills in order to pass their open water courses. Despite the slightly concerning fact that there didn’t seem to be any prospect student divers appearing any time soon, Luke and I agreed that we may as well start running through the skills in the pool to get a good head start and because we still had time to spare by the bucketload.

Because the days were so slow, I think both Luke and I ended up looking forward to the pool sessions quite a lot, but there were times where as I knelt on the tiles underwater and repeated for what felt like the hundredth time a skill, because there was simply nothing else to do that I felt like screaming with frustration underwater. At least we always rounded off each sessions, as usual with the first beer of the day.

The few remaining Scandi Resort staff always remained in high spirits and were a very friendly and hilarious bunch. It seemed to be someone’s birthday at least once a week and this was always the cue to crack out a case of the extremely potent Red Horse beer loved by Filipinos and commence with taking it in turns to pour a glass, down it and pass it to the right; like a joint, so that everyone drank from the same glass. I couldn’t pass by without being offered to partake which I could never resist and because birthday drinks could start from early midday I had to be careful how many times I walked past when the boys were at the Red Horse beer – or the Ginebra gin.

Whenever I asked the lads what they thought about the current situation the response was always that although it was a difficult time and people were obviously worried, we all had to stick together and look out for one another – all of us in that little community of beach living close together, like one big family – which I got the impression I was now to some extent a part of. The warmth and friendliness of the Scandi staff was a continuous reassuring buzz throughout the entire experience and it was impossible to feel down or anxious when spending time with a group of people who never failed to see the funny side of things.

As the weeks rolled into months, lockdown measures in Puerto Galera continued to bounce back and forth between strict and not so strict. Although restaurants, bars and diving remained off the cards and guarded checkpoints along the roads prevented people from leaving the barangay, we were allowed to go to the tiny Castillo supermarket in Sabang village twice a week, provided we bring a quarantine pass, which could be easily acquired from the local community hall.

Because I could get food from the Scandi kitchen and there were still so many crates of beer in my room that parts of it were hard to move about; there was little incentive for me to shop in Castillo but I did still use up the two turns on my quarantine card each week, for after walking along Big Lalaguna, Small Lalaguna and Sabang beaches to get to Castillo, you could carry on past it along the singular road dicing up central Sabang and follow it as it twisted around into a loop back towards Big Lalaguna beach, over a couple kilometres of cracked cement road that were flanked on either side by a sloping landscape of dense vegetation from which came a never ending hiss of insects and tropical bird song: “Ka-waaaa – ka-waaaa” and “sssssssss” and “cha-cha-cha-cha-chaaa”!

In places, the sprawling mass of trees and dense shrubbery peeled back to give keyhole views of the mountainous jungles that rose ever higher further into Mindoro island, as well as glimpses of beautiful Puerto Galera Bay below; the eastern perimeter of which was formed by the western edge of the Sabang peninsular that you were now walking along.

From this last view, the road curved around again to face back towards Big Lalaguna beach; it was a short but steep climb to reach the highest point of the Sabang peninsular: a sharp hill almost directly behind Scandi Resort that overlooked the brief stretch of sloping, jungle clad land running down it, which was dotted by some tin roofed houses and a few rice paddies before melting away into white sand. Beyond, the glistening blue ocean stretched off into the horizon and beyond, broken up only by the lush and sprawling Verde island to the right and further away; some fifteen kilometres off, the jagged and mountainous outline of Batangas’ southern coast on the mighty Luzon island.

I would sit up here for hours, gazing out across the sea and wandering what lay beneath it’s surface and trying to picture the views from the top of the distant tropical mountains. There was no denying that it was a very beautiful place that I had become stranded in.

After ten weeks of not being allowed to dive, news suddenly broke out that the status of the Mindoro Oriental Province, which Puerto Galera was part of, was to be moved from an enhanced community quarantine to a modified general one; which actually meant very few changes in terms of everyday living, barring a few – one of which was that starting from June the third, scuba diving would be allowed once more, provided social distancing measures were still carried out (ironic considering that it was underwater). After so many false alarms that had ended in bitter disappointment, by the time this rumour came around, a lot of the people barely raised an eyebrow.

But, upon that date of the third of June, Luke and I waded out to the sea in front of Scandi Resort in our scuba gear, equipped our fins and masks, snorkelled a little further out, swapped our snorkels for our regulators and then deflated our bcd’s as we descended beneath the light waves drifting into Big Lalaguna Bay. There was that unforgettable hissing sound of air escaping from bcds as they go underwater and then we sank down, juddering bubbles rising up all around us.

Generally, most of Puerto Galera’s best dive sites actually start two beaches over from Big Lalaguna in Sabang Bay and from here they follow the edge of the Sabang peninsular’s eastern top as it curls inwards and back out again like the crown and branches of a tree. It takes just five minutes to reach Sabang Bay from Big Lalaguna where Scandi Resort is located – if your in a scuba skiff that is.

Nobody would walk the dirt sand track from Big Lalaguna to Sabang Bay whilst wearing scuba gear in that searing heat and having to climb the two lots of steep stone steps that curve up and back down the palm tree smattered rocky outcrop that pens Big Lalaguna beach off from Small Lalaguna beach, which you then still have to walk along in order to get to Sabang beach. In our eagerness to go diving however, Luke and I had not waited the extra day to arrange a diving skiff to take us to Sabang Bay – plus we were still half expecting for the permitted diving to turn out to be a false rumour and possibly get nabbed if the coast guard turned up, so we thought it best to keep things low key the first time.

That’s why the very first dive I made in Puerto Galera was entirley within Big Lalaguna Bay, which whilst undeniably more scenic when observed from the shore than Small Lalaguna Bay or Sabang Bay, is not the location of any favourite Puerto Galera dive sites – and in fact we didn’t even visit any of the few official dive sites the bay does have, barely swimming out to ten meters deep. All the same after having spent three months living in Puerto Galera, staying within literally meters of the ocean yet being unable to explore it- and having not scuba dived since 2019 (San Andres in the Caribbean, which I’d stopped off at in between my time in Medellin), I felt ecstatic to be finally on a scuba dive.

The water visibility was superb and there was a dazzling variety of colours from the healthy reefs of corals and sponges and sea anemones and the huge numbers of brightly coloured reef fish swimming among them. We swam over blue staghorn coral, green table coral and red brain coral, the jagged rocks that they clung to also dotted with bright yellow sea squirts, blue starfish and black sea lilies that opened and closed like alien hands.

Gobies nipped off across the sand when we drew close and scores of butterfly fish, clownfish and moorish idols darted this way and that as trumpetfish hung motionless in the water and rainbow coloured nudibranch oozed among the rocks and mantis shrimp scampered between their sand burrows and moray eels snapped their jaws as they poked their heads out of holes and the entire underwater spectacle was performed against an orchestra of the gloops and blurps and trilllps that things sounds like when they move underwater. At one point, a banded sea snake swam past, slithering through the ocean as though it were on land.

Big Lalaguna Bay has several coral nurseries; small metal grids about two meters across that healthy pieces of living coral had been attached to, in the hopes that one day they’ll grow beyond the metal grids to form new reefs; yet even in their infantile stage, the coral nurseries were home to all sorts of critters such as as pygmy seahorses that peeked out nervously from the sessile marine life they hid among and juvenile batfish hovering beneath the grids arches and even one very large and warty, white giant frogfish, who sat motionless and almost perfectly camouflaged against the young hard and soft coral, his great rubbery mouth opening and closing to expose hundreds of tiny sharp fangs waiting to snap up any critter that drifted too close, even if that meant not moving for days. Can you spot him?

Luke had already told me that this would not be the most exciting dive in the world because the primary objective was for of us to get back into the swing of scuba as we hadn’t dived in months – but actually it did turn out to be a little more eventful than either of us anticipated.

When we reached ten meters deep we were unexpectedly hit by a current pushing out to sea; unbeknown to me at the time, it was the strongest current I’d encounter in my entire time at Puerto Galera. For several minutes we puffed into our regulators as we fought against the strong force of nature, covering about a foot a minute with our air rapidly dwindling from the effort; but luckily, strong though the current was we’d only swam several meters into it and were able to stick close to the seabed as we slowly worked our way back against and then out of the current, at which point we decided to end the dive. “Baptism by fire” Luke called it.

However, the real baptism by fire was still to come, for before beginning any of the practical side of my Divemaster training, I still had my three day long PADI Rescue Diver Course to take, for which I’d already completed the emergency first response primary and secondary care course during the long wait, which had involved a handful of simulated scenarios, videos, exams and performing CPR for two minutes on a resuscitation manikin (although because the manikin had no legs, arms, eyes or tongue, I had found myself wandering if the kindest thing to do was actually not to revive him).

The Rescue Diver course itself was a series of lifesaving skills including performing rescue tows at the waters surface, getting unconscious divers out of the water and onto a boat, dealing with panicked divers at the surface (the trick here is to deflate your bcd and sink so they can’t climb onto you; they’ll never follow you underwater because it’s the last place they want to go when in a panic, then surface behind them and grab their tank to keep them still whilst inflating their own bcd; so they don’t need to struggle to stay afloat, meaning they usually calm down as the main cause of panic at the surface is when people can’t stay afloat), safety line throwing, some theory i.e. recognising signs of stress in divers, assessing and responding correctly to different kinds of emergency and about a half dozen more skills that were learnt first separately and then in groups of two or three in anticipation for the final physical exam on day three where I had to string them all together in a simulated emergency scenario:

My eyes darted between my compass and the murky waters around me as I made a classic U pattern search for the missing diver. Where was she? There! Hazel lay motionless on the seafloor and when I tried to gauge a response from her by waving my hand in front of her mask, she did not respond. I wrapped my legs around her air cylinder and then began to inflate her bcd so that we slowly rose to the surface. Several times, I had to deflate and re-inflate her bcd to slow and restart our ascent in order too avoid putting us at risk of the bends.

At the surface Hazel lay face down, still unconscious. I took her hands and crossed them over one another then pulled her wrists to get her face out of the water and then using the pocket face mask stowed in my bcd, I began to provide her with rescue breaths every five seconds as I towed her back to the boat some sixty feet away, removing our bcds a little bit at a time in the five seconds between each rescue breath.

Making sure that both our bcds had been totally removed by the time I got Hazel to the boat, I used one arm to scramble up over the side of the boat with neither grace nor elegance as I used my other hand to hold both of Hazel’s in place on the boat’s gunwale so that she did not float away.

Now in the boat myself, I jumped up and grunted as I heaved to pull her up out of the water by her wrists and laid her upper body down over the boat, before kneeling down to unceremoniously drag the rest of her over. She rolled down into the boat with a wet thumping smack. Hastily I began to perform CPR on her and then assembled an emergency oxygen tank, placing the second facemask over Hazel’s mouth and preparing to turn the 100% oxygen on….

….”And cut”! Said Luke. I collapsed on the floor of the boat, every muscle in my body screaming as I gasped like a fish in need of being thrown into water as well as perhaps some sort of aquatic exorcism and feeling that I probably needed some emergency oxygen of my own as Hazel sat up giggling and a distant voice that seemed far away told me I’d passed my rescue diver course and now the real fun could begin.

And so, finally; commenced the practical aspect of my Divemaster course as over the following weeks Luke taught me many of the skills that I was required to master, in order to actually become a Divemaster. Some skills, like treading water for fifteen minutes whilst holding my arms above the surface, or carrying someone out of the sea onto the beach, or creating an emergency assistance plan listing local emergency service telephone numbers and basic medical procedures and scripts; were easily busted out often several at a time in a single afternoon.

Others took longer; with the very nature of how they were meant to be learnt requiring them to be repeated many times, under different circumstances. Remember the twenty scuba skills I’d been practicing in the Scandi swimming pool over the past couple of months? (The same skills first learnt by student divers taking their open water diver course, now mastered to demonstrable level, including miming how to break each one down into steps as well as the things to remember not to do). Now that we could, Luke and I repeated these skills many times in the open ocean, where they were a little trickier on account of the waves at the surface and the occasional currents beneath it.

Whereas in the pool, we’d only focused on a handful of skills per session; which Luke dictated the pace and structure of, now that we were in open water it was down to me to organise each session; making sure to remember all twenty of the skills as I demonstrated them to Luke who then attempted to repeat each one, before I gave him feedback and when necessary showed him how to do it again.

I say that it was Luke the skills were being demonstrated to, but as we progressed from him running me through the skill circuits to the other way around, my north yorkshirian compadre changed his name from Luke to “Billy Big Balls”, attaining an alarmingly convincing Scottish accent and often interrupting me with cries of “Ya wee bastard”! or “Ah fookin ‘ell”! – or sometimes just unintelligible noises: “Oh ai – eh – och och… argghhhhhh”!!

Billy Big Balls had never scuba dived before and was also something of a moron meaning that he often did things like suddenly over-inflate his bcd to make an uncontrolled ascent forcing me to quickly grab him and deflate his bcd again, or putting his gear on backwards and trying to dive like that or being at the surface and suddenly and un-expectantly booming “Agh-no-a’m-too-fat,-a’m-sinken–HEL-*muffled bubbling shouts*'”!!! before disappearing as he dropped beneath the waters’ surface and sunk to the seabed a few meters below, which I had to stop him from reaching or it’d count as a Billy Big Balls death. On one occasion, he tottered as though drunkenly at the end of the diving skiff and gave a quavering and shrill yelp before falling sideways into the water where he splashed about loudly and uselessly, before I realised he was drowning and had to jump in and rescue him.

It was tough and often hilarious work but as the weeks went by, I knew that I was getting better at each skill whilst also learning to be ever more prepared for any mishaps from Billy Big Balls. However, Luke and I were both aware of the fact that I still needed a real student diver to assist with learning their Open Water & Advanced Open Water courses, in order to pass my own course as a Divemaster. For now though, there were other things to keep me busy; besides just the scuba skill skill circuit being practiced with Billy Big Balls, I had other skills to hone as well.

For one thing, I still had to learn to inflate a surface marker buoy underwater, which is harder than it looks. A surface marker buoy is basically an inflatable, fluorescent orange tube that scuba divers let up via a reel, usually towards the end of a dive, to signal to boat traffic where they will be surfacing in order to avoid being flattened by said boat traffic. Therefore it’s crucial someone in the group always let’s one off during the safety stop at the end of every dive. It isn’t enough to simply puff a bit of air into your surface marker buoy and hope for the best – if you don’t inflate it enough, then there’s a good chance it won’t stand upright out of the water which decreases the likelihood of boats seeing it and increases the probability of you getting hit by one when you surface. Perhaps even more disconcertingly, if when you inflate the surface marker buoy, you don’t let go of the reel that you’ve attached to it, you can get rapidly pulled to the surface which means you’ll now be at risk of getting hit by a boat and decompression sickness (aka the bends) due to your rapid ascent.

So, listen up Diving Squad: to correctly deploy your surface marker buoy, first take it from wherever it’s stored on your bcd and unroll the entire buoy, making sure to have the top end facing upwards. Next, take out your reel and clip it to the handles of the bottom end of the buoy. Now, remove the big clip holding the line in place so that it’s free to unravel (don’t drop the reel!). What you then want to do is have your index finger through the ring in the reel. Always, always make sure that the reel is not wrapped around or caught on any part of you or your gear and don’t hold it; you don’t want to get dragged up to the surface with it when the buoy inflates and shoots upwards!

You can then use your regulator or spare regulator to inflate the marker buoy just a little so that it’s poised upright, before holding it close to your body and straightening it out again to ensure that when it’s fully inflated it does not shoot out sideways and instead goes directly up. At last, you can inflate the buoy fully – don’t be shy, get some air in there nice and quick and be sure to let go as soon as it’s full! Whoosh! The surface marker buoy should shoot to the top (without you) with the reel unravelling as much as it needs to around your index finger. If you’ve inflated the surface marker buoy properly, it should stand fully rigid out of the water when you tug at the reel from below, although you may have to unravel or wind up the reel a couple of times to make sure that it is the right amount of taught. Nice! You surface marker buoy has been deployed.

I’ll be honest with you. The first few times I deployed a surface marker buoy were not very smooth. The next few goes were a little better. But eventually, after doing it at the end of every single dive, I was able to get it like this:

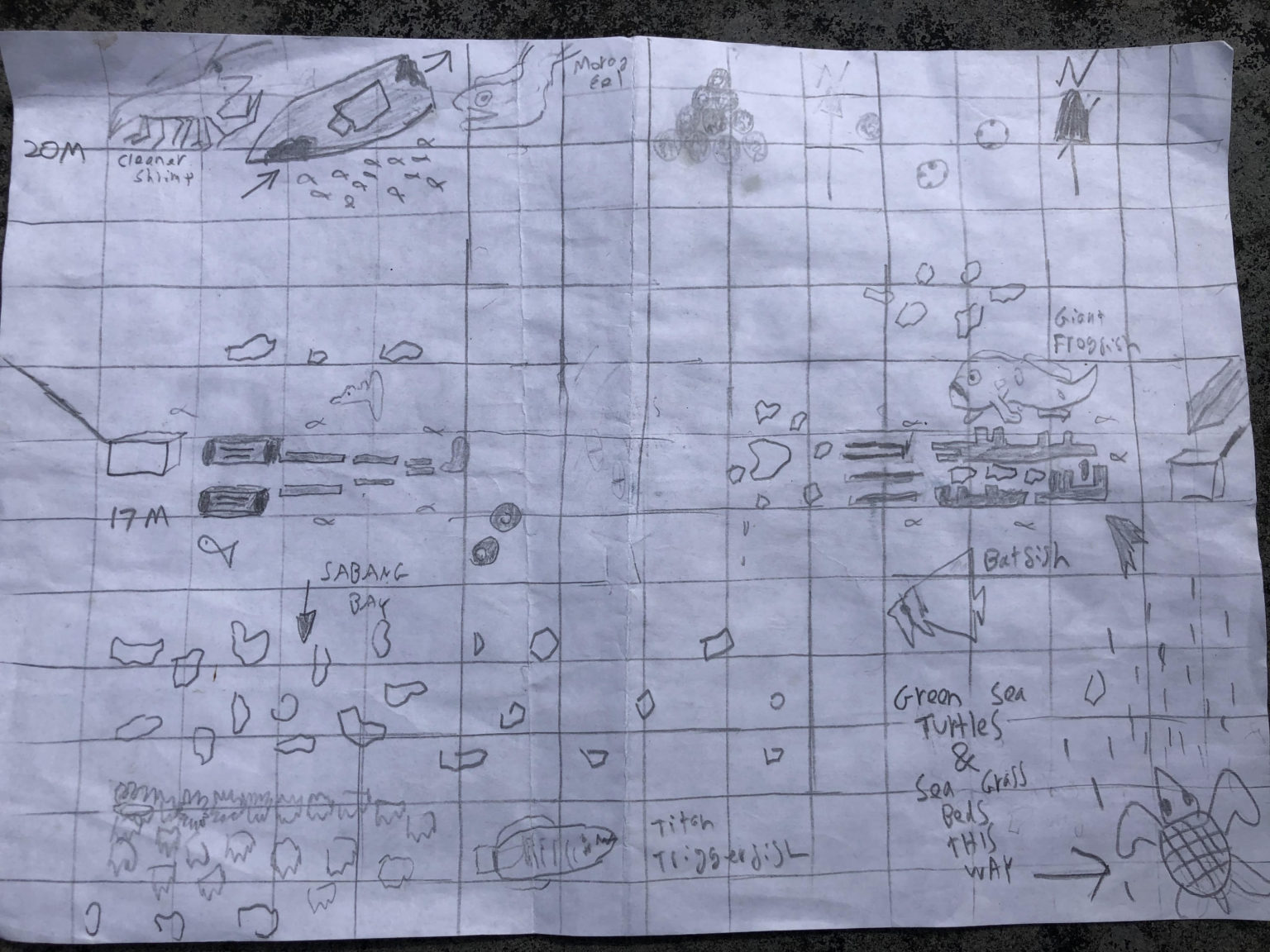

Another cool skill that took multiple days to learn was dive site mapping – which was using a slate, pencil, compass and dive computer to map out an underwater area’s geography and landmarks whilst also recording the distances between things (measured with kick-cycles), changing depths (measured with the dive computer) and other details such as which marine animals could be found where throughout the dive site.

The dive site I mapped was Sabang Wrecks; three deliberately scuttled ships; the first of which lay at seventeen meters deep and was a smallish open timber ship which was now considerably collapsed although part of it’s stern and also the steering wheel were still in tact and covering these was a lot of vibrant hard coral that a jet black giant frogfish which was always there (I called him Kermit), was well camouflaged against. Elizabeth’s Chromodoris nudibranch – slug like mollusks with electric blue bodies dashed up by black stripes and a yellow ring around the edge to indicate them as toxic, crawled over the coral growing out of the wreck as scores of reef fish drifted above them; with larger fish to: about half a dozen pinnate batfish: huge round fish the size of dinner plates with shiny silver bodies, yellow fins and two vertical black bands that ran down over their their glassy white eyes and gills. Every time I dived at Sabang Wrecks, a few of these batfish would follow me from beginning to end, lazily keeping within a few meters but always maintaining a polite distance, no doubt in hopes of bread, for Luke had told me that it was often fed to them by Chinese tourists in normal times and that the mighty but gentle fish had now come to associate scuba divers with it.

Swimming the forty or so meters west from the first wreck to the second, the seabed was bare besides the odd coral coated rock here and there, but it was not lifeless; mantis shrimps poked their heads from their sand burrows; their enormous compound eyes twisting and turning separately as the three rectangular psuedo-pupils stacked on one another within each one also moved (mantis shrimps have the most sophisticated eyes in the animal kingdom; they can detect lightwaves beyond that of the human eye at both ends of the light spectrum; seeing ultraviolet and infrared lightwaves, plus each eye of a mantis shrimp has separate depth perception and they are even the only known species that can detect polarised light.). Bigger and angrier looking faces poked out of the sand to – flat faced, wide mouthed toothy leers belonging to crocodile snake eels whose bodies, often over a meter long, were entirely hidden in the sand as they waited to ambush unsuspecting octopus and finfish.

The second shipwreck, which also lay at seventeen meters and was even more collapsed than the first, was not much more than a flattened hull, although it’s thin, cylindrical twin engines were still in tact. Hard and soft coral sprawled across what remained of this wreck as well as the clusters of rocks dotted around it. Lurking around here were animals such as huge purple stonefish – a relative of giant frogfish which there also more of here to; these ones usually green or grey, unlike the black one named Kermit back at the first wreck (after spending many weeks hiding among the same background, giant frogfish change the colour of their skin to match it, meaning that members of the same species look as different to one another as the underwater formations they live among).

From the second wreck, I turned north and swam for another thirty meters until I was twenty meters deep where there lay the third and final wreck – which was also the most in tact of all three; a steel hull yacht some eighteen meters long and now lying on it’s side.

Although the third wrecks’ topside was covered in a dazzling splash of colours – pinks, purples, yellows, blues and greens from the various corals, sponges, sea lilies and starfish atop it, with many fusiliers swimming around and clusters of lionfish hovering motionless just a few centimetres above the ships exterior and when you swam down to the side of the wreck that was lying against the sand, you saw that the narrow gap of space underneath it was occupied by several large grey moray eels that poked their heads out from underneath and waved their upper bodies from side to side like long dark ribbons in a breeze; my favourite thing about the third of Sabang’s Wrecks’ was that you could actually go inside, swimming through the large crack at the back of it’s stern and finding yourself immersed in a living cloud of many hundreds of tiny bronze fish with splashes of blue across their faces. Dozens of red and white striped cleaner shrimp clambered across the sides of the ships inner hull and when I offered my hand a couple of individuals swam away from their perches looking for bits of dead skin to eat on my fingers. I watched the cleaner shrimp marching up and down my hand for several minutes, wandering about a life spent eating parasites out of larger animals mouths in a sunken ship, before they swam back to their perch and I made my way through the rest of the hull to the other end of the wreck, still encased in the huge school of tiny fish as I exited the wreck by swimming up through the smallish hole at it’s bow end.

I had to map Sabang Wrecks over five different dives, because one person can’t record all the data at the same time. The first time I simply swam around the area, the second I sketched the wrecks and other underwater geological features, such as rock, whilst noting everything’s depths and counting kick-cycles between the wrecks, the third I used a compass to get an accurate idea of the wrecks angular proximity to one another, on the fourth dive I noted the animals around each part of the dive site and the fifth and final time I made a final check to make sure everything was right and accurate. In between each dive, I sketched all of the information I’d recorded on my slate onto a piece of paper with a pencil, which I added to over the successive dives erasing bits and correcting it as I went. It’s not secret that I can’t draw for shit. Despite this, I’ll still share with you the mighty work of art that was my dive site mapping – marvel or scorn at it as you choose:

Yet another big part of the Divemaster course was to broaden overall diving experience. The best way to do this is on fun dives which are relaxed dives with no specific target besides seeing some cool marine life and getting more scuba diving experience. Fun dives are the kinds of dives you make when you go diving with a dive centre, resort for one or more days but not to complete training. That said, the kinds of fun dives you are allowed to go on, depend on the training courses you’ve already completed. You have to at least have completed your open water course to go on a fun dive, whilst some special kinds of fun dives like wreck dives, deep dives and night dives require you to have completed the training for them, which you can do on your advanced open water course or separately. There’s also some kinds of dives you need special training for beyond advanced open water level such as mixed air dives, cave dives and dry suit dives.

Normally, I’d’ve had access to an unlimited number of fun dives during my divemaster course as divemasters in training get to hop on the boat and go on a fun dive for free any time the dive shop has people paying for dives, but currently there was no other guests at Scandi besides me (the only other guest for months had been Brian and he’d stayed for months, but had finally left on the first of June, unfortunately finding out just days after he’d booked his flight that diving would resume seventy two hours after he’d left).

Luckily for me, the kind folks at Scandi Resort agreed to using the diving skiff to take me on fun dives pretty much every other day and when this happened me and my dive buddy would usually feel like we had the entire ocean to ourselves, for although there were a small handful of expats diving here and there, because some ninety nine per cent of Puerto Galeras’ tourists were now absent due to the lockdown and travel restrictions, we rarely saw anyone else at all on our dives; not even another diving boat in the distance.

As I got to explore the many dive sites around Puerto Galera; it became obvious why the people who’d dived in this part of the Philippines, ranted and raved about how incredible it was. I saw mighty coral reefs that sloped up, spread out and even rose around me to form breathing walls and gardens and mighty underwater canyons; living castles of red, purple, pink, blue, green, orange and yellow and I explored many small shipwrecks that had become homes to micro reefs; the largest of which was the thirty meter long Alma Jane; with it’s collapsing deck and twin cabins that you can barely even squeeze your shoulders through and the towering mast still stretching up towards the oceans surface like a giant middle finger and the huge school of batfish that are always found right by it, forming a motionless tower of shimmering silver in the water that does not move until you’re within inches of it and only then to slowly drift away a short distance as a few individuals break away from the main body to swim closer to you in hopes of bread.

I swam over giant clams, each one a meter across as it opened and closed to expose an immense, royal purple or fiery orange mantle within, in the giant clam sanctuary of Puerto Galera Bay and I visited the stretching sea grass beds in Sabang Bay, where many green sea turtles came to feed with their sleepy gazes and dark green, oval shells from which protruded mottled flippers that they used to glide through the ocean as slowly and deliberately as though they had all the time in the world as foot long suckerfish sometimes cruised just a few millimetres beneath them and close by armies of hundreds of horned starfish marched in slow motion.

I explored the mighty underwater labyrinth of towering underwater ridges and walls known as “Canyons” which were spectacularly adorned with corals and sponges that unusually but mesmerisingly were almost entirely of pink, purple and scarlet colouration and were home to great octopus that flashed different colours across their skin and massive fish – huge schools of batfish and fusiliers and titan triggerfish and mighty giant grouper so big they could eat a small shark in one bite.

At almost every dive site, there were huge schools of reef fish of every shape and pattern and colour you can imagine and many more solitary critters hiding among the various reefs, rock formations, wrecks and sandy seabeds around the sabang peninsular: seahorses and pipefish, octopus and mantis shrimp, cleaner shrimp and whip coral shrimp, scorpionfish, frogfish, stonefish, pufferfish, boxfish, cuttlefish, jellyfish, nudibranch, giant groupers, venomous banded sea kraits (banded sea snakes) and sea snake eels which had evolved to resemble the banded sea kraits.

There were things I didn’t recognise at all and others that appeared only for an instant before they shot away again and one time I dived at night and then it became an entirely different world again as most of the day time creatures hid away from sight and the waters became filled with countless thousands of tiny jellyfish and other translucent wormy beings and hordes of tiny shrimp that swarmed around my dive torch like moths to a flame and armies of crabs that marched across the seabed, some of them a meter across and tiny octopus scurried between cover and in places you could find a green sea turtle hidden away beneath a large rock as it slept through the darkness.

You can actually read a lot more about the many dive sites of Puerto Galera in this formal Guide to Puerto Galera Diving I wrote, which also tells you everything you need to know in order to have the best trip there possible. Or, you could check out this short movie of diving in Puerto Galera that I made!

A couple of times, I convinced the odd passing expat to sign up for a fun dive with Scandi Resort and on these occasions I was assigned to them as their dive buddy. On these dives, I learned much about the need to watch guest divers like a hawk to make sure they don’t do things like make an uncontrolled ascent to the surface, bash into coral or simply race ahead with their GoPro. Some times were almost as challenging as handling Billy Big Balls and yet these divers were real!

Now that some of the shops were open up again, including diving gear shops, half way into June I bought my first pieces of scuba gear – a pair of black, RK3 fins, a pair of black diving booties, a black zuunto zoop novo dive computer to show my depth and no deco time as well as record how long I spent on each dive and my entry and exit times, my own surface marker buoy, a black diving mask and snorkel, a black diving compass, a black diving knife and also a second hand, donut bcd which should have been also black but was instead bright green, meaning that I looked somewhat like one of the teenage mutant turtles in it and not batman as I’d been steering towards with the rest of my colour choices. It was great to have some of my own kit and the RK3 fins – which having been designed in collaboration with the US military, had a design that was shorter than most diving fins making them great for tight spaces and frog-kicking, whilst their spring release strap made them extremely easy to put on and take off!

Over two days, I even blasted out my enriched air diver course; which consisted of some theory and two dives and taught me to dive on enriched air – that is, air with a higher nitrogen to oxygen content of the 79% nitrogen, 21% oxygen mix that is found in regular fill scuba diving tanks. By diving on enriched air you can spend more time at greater depths, without the risk of decompression sickness due to the fact that there is far less nitrogen in your bloodstream, which is what causes it in the first place.

However, although mixed air greatly reduces the risk of decompression sickness, it does increase the likelihood of oxygen toxicity which can prove fatal and so it’s extremely important to understand how to know the exact mix of enriched air in your tank, check it, make a visible note of it on a large sticky label that goes on your tank and set the air mix on your dive computer to that which is in your tank, so you know your depth limit for avoiding oxygen toxicity. But after two days I was qualified to dive on enriched air to and completing the course even came with a free “I completed my enriched air course” t-shirt although I didn’t bother to take one.

Exhausted as I was by all the training after months of forced stagnating inactivity with minimal exercise, I was stoked to be finally doing what I had come to Puerto Galera to do and it only gave even more hilarious sources of conversation for myself and Luke as we continued to often game and drink the nights away, albeit at a more refined pace.

But then, half way through my divemaster training; as Luke and I stood on my balcony one golden evening gazing out across the calm ocean at the rugged silhouette of distant Batangas’ mountainous, each of us with an icy beer hand, Luke told me that because he currently wasn’t on a payroll at Scandi Resort, due to the lack of activity, he had been forced to take a temporary IT job elsewhere in Puerto Galera – which came with free accommodation, meaning that he would move there within the next week. He explained to me I would complete the rest of my divemaster course with Rex Medina, who was the filipino dive shop manager at Scandi Resort. Although I’d very briefly met Rex, our conversations had not extended much beyond:

“Hey”.

“Well hello there”

“…”

“Welp, see ya”.

“Bye then”!

“But” said Luke, as he gulped down the last of his beer and cracked open another that had appeared in his hand out of nowhere “you’ll be a better divemaster at the end of this course if you’ve been taught it by different divers. Everyone has their own way of doing things”. “You learn best by putting different experiences and teachings together to form your own style. Don’t look so glum – I’ll still pop by for the odd fun dive with you. Now – rhumsky”? Rhumsky was Luke’s term for cracking open and demolishing an entire 700ml bottle of tandori rum in about an hour. The night blurred into confusion and then was over.

It was the next day that I met Rex Medina properly for the first time. Born on the nearby, tiny Verde island, Rex had moved to Puerto Galera at a young age and now carried a considerable degree of respect among the local Filipinos, who from everything I’d heard, seemed to view him as something of an elder. It was easy to see why.

Rex carried himself and spoke with that certain degree of focused awareness that few individuals attain. He had a muscular build; the result of waking up at five am every morning to run the hilly two kilometres from Sabang to Puerto Galera and back before hitting the jungle gym. His piercing brown and deadly serious eyes hardly ever seemed to blink – as soon as they fixed on me, they seemed to silently growl “don’t fuck around”! I could see that there would be little margin for error and none for messing about under Rex’s instruction.

Hastily, I tried to mentally unwire myself from weeks of hard core banter, comical accents and back and forth insults with Luke. Something told me Rex wouldn’t want to get drunk and play videogames after training at all. He didn’t.

However; like Luke, what Rex did want was to make me the best scuba diver possible; by diligently and at times sharply correcting each and every mistake that I made – no matter how small, whilst explaining how and why to do things differently. Over the following weeks, he patiently showed me how to deploy better surface marker buoys, descend more rapidly on a dive and how to master my buoyancy; having me remove one weight from my belt at a time until I no longer dived with any weights at all. To this day, I still don’t.

We worked on new divemaster skills such as underwater knot tying and different underwater search patterns. These practices I had to later combine to carry out the more challenging task of search and recovery: finding a “lost” and also very heavy object underwater, tying the rope of an underwater airlift bag around it and then inflating the airlift bag enough to give it and the object neutral buoyancy, then towing it to the shore like some sort of underwater helium balloon, gradually releasing air from the bag as it came into shallower waters to avoid it shooting to the top. This was a little tricky, but at least now I know what to do if I ever find a sunken treasure chest on the seabed or a bronze coated canon in a wreck.

By this point, it was nearing the end of June and I had only a few more fun dives left to go before I’d reached the sixty minimum threshold to become a divemaster, including assisting guest divers on the rare occasion we could entice someone else along, usually one of the old boy expats.

I’d ensure they set up their gear correctly (and corrected it for them when they sneakily didn’t), then we’d make our way down to the Scandi skiff where Freddy, the steely gazed boatman, with arms as thick as tree trunks, would un-hich the rope mooring the skiff to the beach and then yank the boats engine into life, skilfully manoeuvring the slim humming vessel between the jagged coral coated rocks protruding from the shallows of Big Lalalguna Bay, as he took us around to wherever we were diving that day, which was most often eastwards into Sabang Bay to explore the likes of the Alma Jane, Sabang Wrecks, the Sea Grass Beds, Sabang Point and beyond Sabang Bay into Monkey Beach, Dugon Wall and West Escarcio or further still: around the far corner of the Sabang Peninsular to Hole in the Wall, Canyons and Fishbowl or even all the way down the long east side of the peninsular to Sinandigan Wall, one of the very furthest dive sites, yet still just twenty minutes via boat from Big Lalaguna.

Other times, Freddy took us in the opposite direction: westwards, around into Puerto Galera Bay where the dive sites were the likes of Giant Clam Sanctuary, Coral Gardens and The Hill. At this point, I knew many of Puerto Galera’s dive sites well, so usually I’d choose the ones I felt most familiar with to take guests to. As well as calling when we entered the water and descended, it was also my job to make sure they stuck together, attend to any problems they had and let up the surface marker buoy during our three minute safety stop at the end of each dive and then make sure they got onto the boat ok.

Rex also stressed to me the art of leading a fun dive; explaining the need not only to ensure divers safety but to also keep a constant eye out for interesting things to show my would be customers; he showed me the best kinds of places to look for certain types of creatures as well as giving me some good tips to entice various animals out of their burrows for a quick peak. Although Rex was forever doing some slick move in the water that involved half snapping, half stabbing his fingers to create spectacular rings of bubbles – of any size he liked and with such accuracy and speed that he could get one to pass right around a slow fish, it was a skill I could never replicate, so I stuck to looking for interesting animals to keep the dives i led rad.

Then came the final two days of my dive master course. On the first, I had to lead a nightmare fun dive in which I guided not only two regular guests but another five of the Scandi resort lads gleefully pretending to be the most difficult guests in the world as we visited sabang wrecks and a chaotic shit show erupted in which everyone deliberately and gleefully had an issue, whether it be incorrectly assembling gear, having a loose cylinder band, not being able to equalise, getting masks flooded, swimming off and getting lost, reaching out to touch marine life or panicking at the surface.

I felt like a cartoon character, my fins a whirlwind blur as I raced from one person to the next and when we finished the dive, I had passed the test but was utterly ruined for the rest of the day, unable to do anything besides lie on my bed groaning.

Then came the last day of my divemaster course – there was just one last thing I had to do: “The Stress Test”. The aim of the stress test is to experience an unusual and difficult scuba diving scenario and respond to it calmly and logically. You have to share air from one regulator, two dives per turn before passing it, with another diver as you take off your fins, masks and bcds and swap them with each other, donning one another’s gear and then doffing it and swapping it all back again. I was not allowed to plan or practice for this beforehand and only learnt from Rex afterwards that half of all the divemasters he’d taught had balked and broken for the surface during this final exercise, thereby failing it. Check out the video below to see how things went when I did the stress test for the first time with Rex:

And with that, I had become a divemaster. It was far from the manner in which I’d expected to when I’d come to the Philippines four months ago – I’d have never imagined that I’d not be able to visit anywhere besides Puerto Galera, nor that I’d complete my training amidst a global pandemic after months of waiting as the only guest at a ghost resort. None of this mattered that day. I was proud to be a divemaster and felt lucky to have been in such a beautiful place doing something that I loved so much for the first half of 2020 whilst surrounded by awesome people.

The one last thing that remained of the course, was the celebratory party that marked it’s end, so that same afternoon, myself, Rex, Freddy and a load of the other Scandi Lads all met up on the resorts’ sky bar and proceeded to consume large quantities of beer and barbecued meat and fried rice, the feast lovingly prepared by Ivan the head chef, who was always laughing hysterically at something or other. Gary was there to; smoking like a chimney and telling stories and then after a while Luke appeared, having come over from the new place he was staying at, to slap me on the back and congratulate me and guzzle beer till it ran down his chin, never once so much as staggering. It was good to see the crazy yorkshireman once more. For the first time, I saw Rex drink and learned to my astonishment that he was in his mid fifties, despite the fact I had thought he could only be in upper thirties! I guess that must’ve been the effect of all that sunshine, exercise and diving.

Music blared from my speakers and the scandi boys roared with laughter and hours of raw footage that I’d shot whilst diving played on loop on the big tv screen that was against the sky bar wall and the sky reddened and the drinks flowed and the barbecued meat dwindled. Very soon, we were all very far gone and shouting and laughing and leaning against one another’s shoulders telling absurd jokes as the stars in the clear night sky swirled overhead like a mad, lit up carousel and many words of hope and inspiration were said but honestly I don’t remember many of them in great detail; it’s all just a happy blur.